Dr. T.K. TRAN, MD | 16/7/2014

(Defend the Defenders)

The Case of Mr. Dinh Dăng Dinh (1963-2014)

Mr. Dinh Dang Dinh was a Vietnamese veteran who later taught chemistry in schools. If he had done nothing but performing his military duties and teaching chemistry to attentive students, no one in Vietnam and other countries would have heard about him. However, Mr. Dinh posted blogs about environmental impacts of the bauxite mines on the Central Highlands of Vietnam and the people’s aspiration for freedom and democracy. The Vietnamese government could not tolerate that and arrested him in October 2011. A year later, a court sentenced him to six years in prison. While imprisoned, he was diagnosed with stomach cancer. He passed away on 3 April 2014 (1).

A patient’s medical records were treated as if they were a state secret

A patient’s medical records were treated as if they were a state secret

After his diagnosis, government agencies kept Mr. Dinh and his family in the dark about his illness. The family’s request for the medical records was rejected by the prison administration on the ground that they were not responsible for tracking a prisoner’s medical status but the hospital where the patient has been being treated (2). The family’s request was also denied by the hospital on the ground that they could not release the records without approval of the Ministry of Public Security. Unfortunately, the Ministry did not respond to the family’s request. The situation has not changed until now. Mr. Dinh’s medical records are still treated like a state secret. The European and American embassies in Hanoi have sent letters criticizing the Vietnamese government on this issue (3).

Reconstruction of the events associated with this medical records case

This article is an attempt to present the events surrounding Mr. Dinh’s illness in spite of the lack of official records. We relied on information provided by Mr. Dinh’s family, including information that the family had already made public and new information from private sources.

What caused Mr. Dinh’s stomach cancer?

Physicians are frequently faced with questions from patients: “Why me? What caused this disease?” In many cases, physicians have answers, e.g. chain smoking led to lung cancer.

There is no easy answer in the case of stomach cancer because there could be a number of causes. The primary cause for stomach cancer is a virus, Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter pylori infection always causes chronic stomach ulcer. As the disease progresses, it can shrink the inner stomach lining (mucosa) in some patients. Environmental factors and patient’s risk factors could bring about stomach cancer. Risk factors include unhealthy diet, pre-existing ulcers, or a history of stomach cancer in the patient’s family (4).

In Mr. Dinh’s case, we cannot determine the cause without examination and detailed knowledge of his health before the onset of cancer. His detention was not the direct cause of cancer.

A stealthy and deadly progression

Stomach cancer is dangerous because its symptoms are many and do not point to the primary cause. However, danger signs include coughing up blood, bloody stool, frequent abdominal discomfort, nausea, lack of appetite, and weight loss.

In October 2011, Mr. Dinh began a 10-day hunger strike to protest against his torture by Public Security officers who tried to force him to plead guilty of the false charges. At that time, he had already been vomiting blood in large quantities. His wife requested prison authorities to let him receive medical care but they denied her request. He continued to feel weak and feel pressure on his abdomen. Prison authorities did not heed the symptoms of recurring abdominal pain. Worse, they had him spend a few weeks in the mental hospital in Bien Hoa. Could the prison authorities have thought that his illness had a psychological basis?

On 14 April 2013, he had to be taken to the emergency ward of Dong Xoai Hospital. They sent him back to prison the following day despite his abdominal pains.

On 3 September 2013, following a collapse, his conditions deteriorated badly. They moved him from An Phuoc Prison to the “April 30” Hospital in Saigon, that belongs to the Ministry of Public Security. Nearly two years following his experiencing a bleeding stomach ulcer, that was the first time they provided a thorough medical examination. The endoscopy revealed tumors in his stomach (5).

The hospital admitted him on 5 September 2013.

Is Mr. Dinh’s cancer at Stage III or IV?

On 18 September 2013, surgeons removed ¾ of Mr. Dinh’s stomach and nearby lymph nodes. When surgeons decide to remove ¾ of a patient’s stomach, it can be assumed that the tumors are near the pylorus, because if the tumors were closer to the esophagus, the surgeons would decide to remove the entire stomach.

Mrs. Dinh, the patient’s wife, said: “On 2nd of October I asked his surgeon about the situation. The surgeon said that my husband suffered from stomach cancer and the disease had metastasized. When I inquired about the lab tests, he said that they were ongoing”. Mr. Dinh’s daughter said that his physicians did not tell the family if the tumors were malignant or not at the time. They only revealed that they were malignant a month later.

On December 16, 2013, Colonel Phan Dinh Hoan, warden of An Phuoc Prison wrote to Mrs. Dinh: “…based on summary reports No. 78 of 21 October 2013, and No. 96 of 26 November 2013 by April 30 Hospital … Convict Dinh has stomach cancer that has spread to his lymph nodes (but it is at Stage 3, not yet the final stage)”(5).

Meaning of Stage III and Stage IV

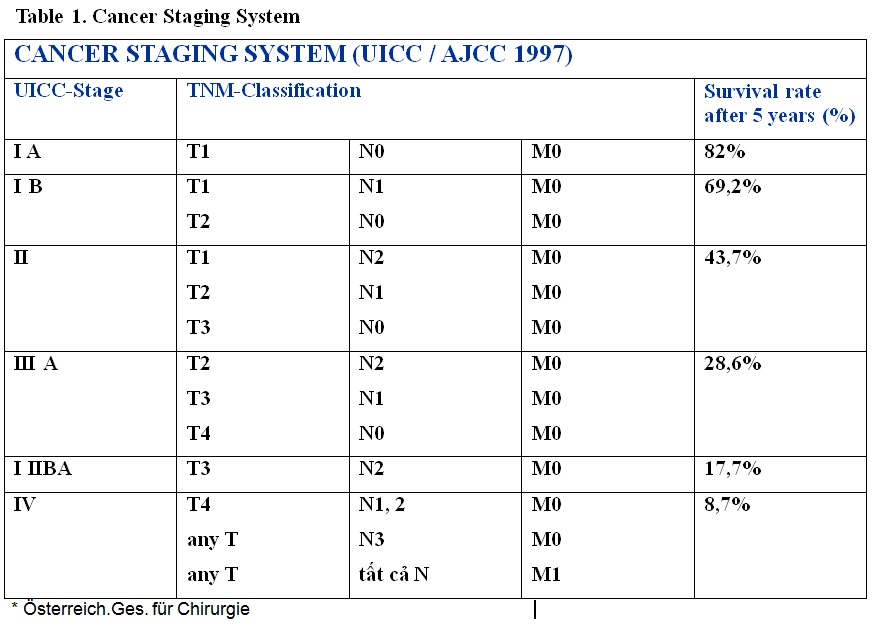

Table 1 shows the system used to classify cancer stages. The disease severity is determined by the expansion of the tumors (T1 -T4), the number of affected lymph nodes (N0-N3), and the existence of metastasis (M) in other organs such as liver, lungs, bones, etc. The determination of a cancer patient’s stage is crucial, not only for selecting the course of treatment, but also to the decision whether the prisoner should be released or not (6).

The factors that determine stage IV are the presence of distant metastasis (M1) and the number of affected regional lymph nodes (N1/N2).

When more than 15 lymph nodes are affected (N3), the staging system determines that the cancer is at Stage IV, regardless of the spread of tumors or whether distant metastasis has occurred or not.

Stage III implies that the cancer has not spread to nearby organs and only a few lymph nodes are affected, without distant metastasis. Please see Table 1.

When physicians found out that Mr. Dinh had cancer, was it Stage III or IV (final stage)? We have yet to get to the correct answer.

Postoperative period: an extremely painful period for the patient

Shortly after the operation, Mr. Dinh seemed to improve. They moved him back to An Phuoc Prison. However, his health deteriorated and his stomach bled frequently. His daughter said that her father looked worse and worse each time a family member visited him.

On 4 November 2013, they moved him back to April 30 Hospital in Saigon, 120 km from An Phuoc Prison, for the first chemotherapy session. After the treatment, they returned him to the prison where he suffered very much from side effects of the treatment, including fever, abdominal pains, and severe vomiting. They took him to the hospital again. Three days later, they returned him to prison where he resumed vomiting. He revealed that prison staff stopped giving him the medication that hospital staff was giving him while he was in the hospital.

On 25 November 2013, they moved him to April 30 Hospital for a second chemotherapy session. After they returned him to the prison, he suffered from stomach bleeding during 10 days. The attending physician thought that his sutures got infected and gave him medicine for that.

On 17 December 2013, they took him to April 30 Hospital for a third chemotherapy session. At the hospital, he requested hospital staff to tell him about his situation and the names of the medical drugs that they had been giving him. When hospital staff refused, he declined the proposed chemotherapy. On 18 December, the American, Canadian, Australian, and European Union embassies sent letters to the Vietnamese government in which they expressed their concern for Mr. Dinh and their wish to see him released from prison (3). The government moved him back to An Phuoc Prison on December 25, 2013.

His rapidly deteriorating condition led them to bring him to Section 4 of the Cancer Hospital in Saigon on 6 January 2014. In that section, each bed had to be shared by three to four patients. His family requested another room. A day later, he was moved to the palliative care section reserved for terminal patients. Four patients share a room with four beds. It cost his family 250,000 Dong (VN currency unit) per day additionally. Three Public Security officers always stayed near his bed, supplemented by a camera, to watch him 24 hours daily, in spite of his being so weak that he could not even sit up to vomit or could not leave his bed when urinating or defecating.

During the first two weeks in palliative care, hospital staff examined Mr. Dinh using a variety of instruments, but did not provide any noteworthy treatment. When his relatives asked about the treatment, physicians tried to deflect the question or replied that they had to consult with physicians who had treated him at April 30 Hospital, or answered arrogantly: “if you stop asking for his medical records, we will give him chemotherapy”. Mr. Dinh suffered from kidney malfunction in that period and urinated with much difficulty.

On 13 February 2014, hospital staff gave him his third chemotherapy session, as the government planned to return him to prison after the session. However, that night he suffered greatly from side effects, and vomited so much blood that his daughter described as “filled a small bucket” (7). He was allowed to remain in the hospital.

On 15 February 2014, the government issued an order for a 12-month suspension of his prison sentence. From then on, they removed the Public Security guards and the monitoring camera from his room.

On 17 February, they moved him from the palliative care section to Section 4, making him share a bed with three other patients, under terrible conditions. Physicians said that the remaining part of his stomach was like “a jungle and could no longer function”. He could no longer eat because the food could no longer be absorbed, resulting in his vomiting. His kidneys failed more and more.

After a period of intravenous feeding, Mr. Dinh decided to try traditional (oriental) medicine instead of Western medicine. After a few days of using traditional medicine, he got no better.

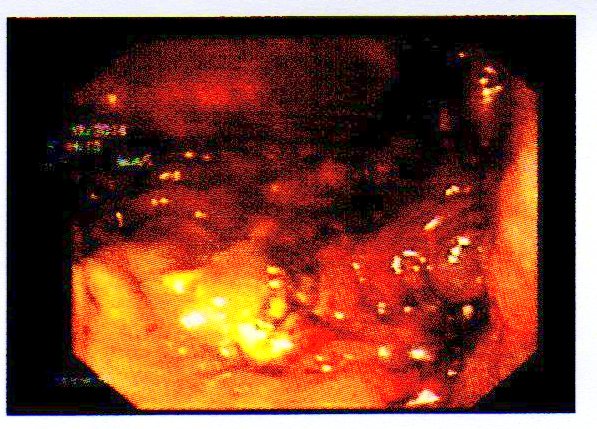

In mid-March 2014, Mr. Dình’s family took him to Columbia Asia, a private, foreign-owned hospital in Saigon, to seek help for him. Hospital staff put him in intensive care and gave him a comprehensive examination. An endoscopy showed that tumors had re-formed in the remaining part of his stomach (8).

Figure 1. 13 March 2014 endoscopy photo by Columbia Asia Hospital showing newly formed tumors in the remainder of Mr. Dinh’s stomach.

Hospital staff advised the family that there was no more hope to cure him. As Mr. Dinh wished, his family brought him home toDak Nong where he passed away 18 days later on 3 April 2014.

A retrospective look at the patient’s disease progression and his diagnosis and treatment: regrettable failures and unanswered questions

As an impartial observer who is not close to Mr. Dinh, a recap of his disease progression raises a number of obvious questions.

1. Why did it take so long to start examining him and diagnose his illness?

In early November 2011, Mr. Dinh started vomiting and passing blood in his stool. Mrs. Dinh, his wife, recounted: “On 8 of November, I visited my husband in prison. He was bleeding from his stomach. I returned home to write a request to have my husband to be examined and treated at a hospital. I sent the request to prison authorities. However, they only let him be examined and treated at the prison’s medical station. Ms. Thao, Mr. Dinh’s daughter, said that the medical station was merely an isolation cell with a stone platform used as a bed. The only medical equipments consisted of a stethoscope and a blood pressure monitor. The only treatment was an injection to relieve pain in case a patient felt pain, but there was no diagnosis of the root cause. Nothing else was offered in terms of treatment or diagnosis.

Any physician would have felt that a bleeding stomach called for emergency treatment because the symptom indicates an ulcer or even a case of stomach cancer. In serious cases, bleeding from the stomach could lead to fatal hemorrhage if not properly treated on time. Endoscopy would have been the simplest, yet most effective approach to diagnosing the patient. An endoscopy administered in November 2011 would have diagnosed his cancer nearly 2 years earlier, when it was still Stage I or II and not Stage III or IV cancer. Timely treatment would have given him 43,7% to 82% chance for surviving five or more years, depending on whether his cancer was Stage II or I, as the previously mentioned table shows. The most egregious misfortune for him and his family was perhaps the authorities’ complete disregard for the health and life of a prisoner, a disregard that made them blind to Mr. Dinh’s life-threatening symptoms. Prison authorities were wrong as they sent him to the mental hospital in Bien Hoa for two weeks of treatment, believing that his symptoms were more mental than physical.

- Why did physicians in April 30 Hospital conclude that his cancer was Stage III?

Colonel Hoan, the warden of An Phuoc Prison, informed the patient’s family: “….based on summary reports No. 78 of 21 October 2013, and No. 96 of 26 November 2013 of the April 30 Hospital…Convict Dinh has stomach cancer that has spread to his lymph nodes (but it is at Stage 3, not yet the final stage)(5)”.Stage III implies that cancer has not spread to nearby organs and only a few lymph nodes are affected, without distant metastasis. A postoperative examination of the stomach section that had been removed and an examination of neighboring lymph nodes in the patient’s body could have shown whether cancer had spread to nearby organs (e.g. the pancreas), and the number of affected lymph nodes. If one wanted to determine the existence of distant metastasis, one should use CT or MRI to examine the lungs and abdomen, and examine the bones by taking scintigrams.

When April 30 Hospital classified Mr. Dinh’s cancer as Stage III, it indirectly pushed him back to the prison in spite of the severity of his disease. The hospital staff did not conduct the examinations cited above (according to Mr. Dinh’s relatives) and therefore could not have determined that Mr. Dinh’s cancer was at Stage III (7). The family’s efforts to obtain his medical records in order to learn more about his diagnosis and treatment were not successful.

The only proper examination he received was at the Cancer Hospital of Saigon. The decision to suspend his prison sentence was probably based on the Cancer Hospital’s diagnosis showing the severity of his disease.

3. Why hadn’t they administered chemotherapy before his operation?

- Dinh recounted the Cancer Hospital’s chronology:“They examined him on 5 September, admitted him on 9 September and operated on him on 18 September” (6).Once a physician has found a tumor in a patient’s body, he should decide on a course of treatment. If the tumor was bleeding, he must operate immediately to prevent strokes. If the tumor was not bleeding, the physician would have time to plan for the treatment. If the tumor was large (“mango size” as in Mr. Dinh’s case)(7), the latest medical guides (11)(13) suggested administering chemotherapy before the operation so that the tumor will have shrunk by the time the physician cuts it out, for better results. The chemotherapy should resume after the operation. Mr. Dinh’s tumor was not bleeding and there was no urgent need for an operation. However, why did the physician wait 14 days before operating even when he had ruled out chemotherapy before the operation? The medical records are the only place where one may find the answer because the physician must have written down all the facts behind his decision.

4. Was the removal of ¾ of Mr. Dinh’s stomach a success?

The hospital considered the operation in which ¾ of his stomach had been removed a success once he regained consciousness after the operation. Yet, what did this achieve? Shortly after the operation, his condition got worse and worse. From November 2013, two months after the operation, he again vomited blood. His physician thought that the sutures got infected. However, vomiting blood could be the symptom of something else, namely the operation failed to remove all the cancer cells and cancer continued to spread, causing the remainder of his stomach to bleed. The endoscopy at Columbia Asia Hospital on 13 March 2014 showed a tumor in the remaining portion of the stomach, confirming this hypothesis. This raises the third question: If chemotherapy had been used before the operation to shrink the tumor, perhaps the operation would have removed all the cancer and Mr. Dinh would have been spared the terrible bleeding episodes following the operation that traumatized him and his loved ones. Only the complete removal of all cancerous tissue could have qualified the operation a total success.

5. Why did Mr. Dinh’s kidneys fail?

After the operation, he had been in pain during the last few months of his life, pain caused by terminal stage cancer, compounded by the side effects of chemotherapy. Moreover, shortly after the second chemotherapy session, his failing kidneys caused him considerable difficulty when urinating. Was his kidney condition unrelated to his treatment or a side effect of chemotherapy? The chemicals that destroyed cancer cells could very well have attacked his kidney cells, hampering their function (12).

Whatever the cause of the kidney failure, the problem was like the last link of a chain, with the chain being the progression of symptoms and the patient’s cancer.

6. Why did Mr. Dinh and his relatives have no access to his medical records?

Treatment can be more effective when a patient has sufficient information about his disease. An example is diabetes. Medical personnel not only encourage diabetic patients to learn about their disease, they also coach the patients on learning more and more. Patients with severe cases of cancer have a great desire to learn about their disease. A patient who is knowledgeable about his disease benefits psychologically and his treatment may have a higher chance of success. International research confirmed this fact (4). Mr. Dinh and his family are no exception. When hospital staff withheld medical records and the names of the medicines provided to the patient, without stating the reason for such secrecy, they diminished the patient’s faith in his physicians and medicines. Mr. Dinh refused the third chemotherapy session proposed by April 30 Hospital. Subsequently, after he entered the Cancer Hospital, he left that hospital some time later.Mr. Dinh tried traditional medicine for a period, and later entered a private hospital, Columbia Asia, after he was released from prison. His actions and his relatives’ suspicion of poisoning by prison staff (10) pointed to a profound distrust of the medical care provided by the government and of the government’s respect for the law.

Why does the government withhold a detainee’s medical records? There has been no answer to this question, and the same is true for many other questions related to Vietnam’s important national issues.

The government’s handling of the temporary suspension of the sentence for a very sick prisoner

Colonel Phan Dinh Hoan, the warden of An Phuoc Prison, in a document dated 16 December 2013, cited a document with an unusually long number, Circular 03/2013/TTLT-BCA-TANDTC-VKSNDTC-BQP-BYT issued on 15 May 2013. The circular provided guidance on the procedure for suspending a prisoner’s sentence as follows (5):

Conditions under which a suspension may be considered: “Prisoner’s illness is so severe that he cannot serve his sentence, and if he served it, his life would be in danger. Consequently, a suspension of his sentence should be granted to allow him to receive medical care…This provision applies to severe illnesses such as last stage of cancer, paralysis, tuberculosis that resists antibiotics….cannot independently perform bodily functions, andwhose prognosis is poor, and probability of dying is high, or has been diagnosed with one of the diseases that the medical commission, a provincial hospital or military district hospital (or higher level hospitals) has determined in writing that the patient is in grave danger to his life.”

The circular might have been intended to show mercy in allowing severely sick prisoners to return home for medical care. Until shortly before the document was issued, i.e. before 15 May 2013, did sick prisoners have to serve their sentences until death? However, a close examination of the language of the document reveals that government officials still have much leeway in keeping sick prisoners or releasing them for medical treatment. First, the guidance has no mandatory character: a suspension may be considered(not guaranteed). Second, the government has latitude in defining the severity of sickness. The document cited the last stage of cancer as an example of being gravely ill although many who suffer from breast cancer did survive for several years after being diagnosed with last stage cancer. Prison authorities deemed Stage III cancer with poor prognosis to be not severe enough. The decision showed that prison authorities neglected to consider the varying malignancy and prognosis among different types of cancer. In December 2013 Colonel Hoan relied on the circular to refuse to release Mr. Dinh on the ground that his condition was not yet life threatening. In fact, Mr. Dinh died less than 4 months later, proving that the government’s decision was wrong.

Analyzing past events to avoid future mistakes

Mr. Dinh Dang Dinh has passed away. There are enough facts supporting the belief that he would have lived longer had he been in a prison where authorities were more humane, showed more concern, and allowed timely medical examination and appropriate treatment. There are many gravely ill prisoners of conscience and “regular” prisoners in Vietnam’s prisons. We must not let future tragedies happen like the one that took Mr. Dinh’s life.

The government must show appropriate concern to detainees’ medical symptoms and ensure prompt and sufficient medical examination. Prisons must stop the current practice of cursory examination and prescribing pain-relief medicine without digging into the root cause of such symptoms.

The government must ensure that detainees receive the same level of medical care as other citizens. The government must treat gravely ill prisoners more humanely and enable conditions under which their relatives can care for them and get them proper medical treatment.

The government must give the patients and their loved ones complete information about the disease and the course of treatment, including medicines. It is each patient’s basic right and the right of his/her family to have complete information about his or her disease. The more information a patient has about his/her disease, the higher the probability of cure. Withholding medical information can be construed as a subtle form of mental torture.

Concluding remarks

The author is grateful to Mr. Dinh Dang Dinh’s family and Mr. Vu Quoc Dung

(VETO! Human Rights Defenders’ Network) for their assistance and provision of documents, photos, and other information. While we have tried to use all the resources at our disposal and maintain the highest level of objectivity, there can be omissions and even inaccuracies. A complete and error-free report is possible only after the Vietnamese government releases all of Mr. Dinh’s medical records, at least to his family.

Until then, the government’s lack of humanity in its treatment of prisoners will continue to be an issue in the eyes of many.

This report was prepared in Vietnamese and in German, and will be released in Germany and several other countries. TKT(MRVN).

(*) Remark: the Vietnamese version of this study was posted on http://boxitvn.blogspot.de/2014/05/khi-mot-benh-uoc-dau-kin-nhu-la-bi-mat.html, on May 4, 2014

References

(1)http://www.amnesty.org/en/news/death-activist-dinh-dang-dinh-should-be-wake-call-viet-nam-2014-04-04

(2) An Phuoc Prison’s document No 926-CV/AP, December 24, 2012

(3) http://www.rfa.org/english/news/vietnam/dinh-dang-dinh-12202013161509.html

(4) http://www.krebsgesellschaft.de/download/s3_magenkarzinom_2011_langversion.pdf

(5) An Phuoc Prison’s document No. 907/CV-AP of December 12, 2013

(6) http://www.rfa.org/vietnamese/in_depth/teacher-conscience-in-critical-condition-tt-10082013171218.html

(7) Information from a private source.

(8) Results of endoscopy performed on March 13, 2013, Klinik ColumbiaAsia, Saigon

(9) http://www.rfa.org/vietnamese/in_depth/teacher-conscience-in-critical-condition-tt-10082013171218.

(10) htmlp://www.bbc.co.uk/vietnamese/vietnam/2014/04/140405_dinhdangdinh_funeral.shml

(11)http://www.pathologie-guetersloh.de/informationen/leitlinien-empfehlungen-und/magen-git-leitlinien-empfeh/s3-leitlinie-magenkarzinom.pdf (66. Empfehlung)

(12)http://http://www.krebsinformationsdienst.de/behandlung/chemotherapie-nebenwirkungen.php

(13)www.krebsinformationsdienst.de/tumorarten/magenkrebs/behandlungsverfahren.php#inhalt17

Height Insoles: Hi, I do believe this is an excellent site. I stumbledupon …

http://fishinglovers.net: Appreciate you sharing, great post.Thanks Again. Keep writi…

Achilles Pain causes: Every weekend i used to pay a quick visit this site, as i w…

July 16, 2014

The government treats a sick detainee’s medical records like a state secret

by Nhan Quyen • Dinh Dang Dinh

Dr. T.K. TRAN, MD | 16/7/2014

(Defend the Defenders)

The Case of Mr. Dinh Dăng Dinh (1963-2014)

After his diagnosis, government agencies kept Mr. Dinh and his family in the dark about his illness. The family’s request for the medical records was rejected by the prison administration on the ground that they were not responsible for tracking a prisoner’s medical status but the hospital where the patient has been being treated (2). The family’s request was also denied by the hospital on the ground that they could not release the records without approval of the Ministry of Public Security. Unfortunately, the Ministry did not respond to the family’s request. The situation has not changed until now. Mr. Dinh’s medical records are still treated like a state secret. The European and American embassies in Hanoi have sent letters criticizing the Vietnamese government on this issue (3).

Reconstruction of the events associated with this medical records case

This article is an attempt to present the events surrounding Mr. Dinh’s illness in spite of the lack of official records. We relied on information provided by Mr. Dinh’s family, including information that the family had already made public and new information from private sources.

What caused Mr. Dinh’s stomach cancer?

Physicians are frequently faced with questions from patients: “Why me? What caused this disease?” In many cases, physicians have answers, e.g. chain smoking led to lung cancer.

There is no easy answer in the case of stomach cancer because there could be a number of causes. The primary cause for stomach cancer is a virus, Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter pylori infection always causes chronic stomach ulcer. As the disease progresses, it can shrink the inner stomach lining (mucosa) in some patients. Environmental factors and patient’s risk factors could bring about stomach cancer. Risk factors include unhealthy diet, pre-existing ulcers, or a history of stomach cancer in the patient’s family (4).

In Mr. Dinh’s case, we cannot determine the cause without examination and detailed knowledge of his health before the onset of cancer. His detention was not the direct cause of cancer.

A stealthy and deadly progression

Stomach cancer is dangerous because its symptoms are many and do not point to the primary cause. However, danger signs include coughing up blood, bloody stool, frequent abdominal discomfort, nausea, lack of appetite, and weight loss.

In October 2011, Mr. Dinh began a 10-day hunger strike to protest against his torture by Public Security officers who tried to force him to plead guilty of the false charges. At that time, he had already been vomiting blood in large quantities. His wife requested prison authorities to let him receive medical care but they denied her request. He continued to feel weak and feel pressure on his abdomen. Prison authorities did not heed the symptoms of recurring abdominal pain. Worse, they had him spend a few weeks in the mental hospital in Bien Hoa. Could the prison authorities have thought that his illness had a psychological basis?

On 14 April 2013, he had to be taken to the emergency ward of Dong Xoai Hospital. They sent him back to prison the following day despite his abdominal pains.

On 3 September 2013, following a collapse, his conditions deteriorated badly. They moved him from An Phuoc Prison to the “April 30” Hospital in Saigon, that belongs to the Ministry of Public Security. Nearly two years following his experiencing a bleeding stomach ulcer, that was the first time they provided a thorough medical examination. The endoscopy revealed tumors in his stomach (5).

The hospital admitted him on 5 September 2013.

Is Mr. Dinh’s cancer at Stage III or IV?

On 18 September 2013, surgeons removed ¾ of Mr. Dinh’s stomach and nearby lymph nodes. When surgeons decide to remove ¾ of a patient’s stomach, it can be assumed that the tumors are near the pylorus, because if the tumors were closer to the esophagus, the surgeons would decide to remove the entire stomach.

Mrs. Dinh, the patient’s wife, said: “On 2nd of October I asked his surgeon about the situation. The surgeon said that my husband suffered from stomach cancer and the disease had metastasized. When I inquired about the lab tests, he said that they were ongoing”. Mr. Dinh’s daughter said that his physicians did not tell the family if the tumors were malignant or not at the time. They only revealed that they were malignant a month later.

On December 16, 2013, Colonel Phan Dinh Hoan, warden of An Phuoc Prison wrote to Mrs. Dinh: “…based on summary reports No. 78 of 21 October 2013, and No. 96 of 26 November 2013 by April 30 Hospital … Convict Dinh has stomach cancer that has spread to his lymph nodes (but it is at Stage 3, not yet the final stage)”(5).

Meaning of Stage III and Stage IV

Table 1 shows the system used to classify cancer stages. The disease severity is determined by the expansion of the tumors (T1 -T4), the number of affected lymph nodes (N0-N3), and the existence of metastasis (M) in other organs such as liver, lungs, bones, etc. The determination of a cancer patient’s stage is crucial, not only for selecting the course of treatment, but also to the decision whether the prisoner should be released or not (6).

The factors that determine stage IV are the presence of distant metastasis (M1) and the number of affected regional lymph nodes (N1/N2).

When more than 15 lymph nodes are affected (N3), the staging system determines that the cancer is at Stage IV, regardless of the spread of tumors or whether distant metastasis has occurred or not.

Stage III implies that the cancer has not spread to nearby organs and only a few lymph nodes are affected, without distant metastasis. Please see Table 1.

When physicians found out that Mr. Dinh had cancer, was it Stage III or IV (final stage)? We have yet to get to the correct answer.

Postoperative period: an extremely painful period for the patient

Shortly after the operation, Mr. Dinh seemed to improve. They moved him back to An Phuoc Prison. However, his health deteriorated and his stomach bled frequently. His daughter said that her father looked worse and worse each time a family member visited him.

On 4 November 2013, they moved him back to April 30 Hospital in Saigon, 120 km from An Phuoc Prison, for the first chemotherapy session. After the treatment, they returned him to the prison where he suffered very much from side effects of the treatment, including fever, abdominal pains, and severe vomiting. They took him to the hospital again. Three days later, they returned him to prison where he resumed vomiting. He revealed that prison staff stopped giving him the medication that hospital staff was giving him while he was in the hospital.

On 25 November 2013, they moved him to April 30 Hospital for a second chemotherapy session. After they returned him to the prison, he suffered from stomach bleeding during 10 days. The attending physician thought that his sutures got infected and gave him medicine for that.

On 17 December 2013, they took him to April 30 Hospital for a third chemotherapy session. At the hospital, he requested hospital staff to tell him about his situation and the names of the medical drugs that they had been giving him. When hospital staff refused, he declined the proposed chemotherapy. On 18 December, the American, Canadian, Australian, and European Union embassies sent letters to the Vietnamese government in which they expressed their concern for Mr. Dinh and their wish to see him released from prison (3). The government moved him back to An Phuoc Prison on December 25, 2013.

His rapidly deteriorating condition led them to bring him to Section 4 of the Cancer Hospital in Saigon on 6 January 2014. In that section, each bed had to be shared by three to four patients. His family requested another room. A day later, he was moved to the palliative care section reserved for terminal patients. Four patients share a room with four beds. It cost his family 250,000 Dong (VN currency unit) per day additionally. Three Public Security officers always stayed near his bed, supplemented by a camera, to watch him 24 hours daily, in spite of his being so weak that he could not even sit up to vomit or could not leave his bed when urinating or defecating.

During the first two weeks in palliative care, hospital staff examined Mr. Dinh using a variety of instruments, but did not provide any noteworthy treatment. When his relatives asked about the treatment, physicians tried to deflect the question or replied that they had to consult with physicians who had treated him at April 30 Hospital, or answered arrogantly: “if you stop asking for his medical records, we will give him chemotherapy”. Mr. Dinh suffered from kidney malfunction in that period and urinated with much difficulty.

On 13 February 2014, hospital staff gave him his third chemotherapy session, as the government planned to return him to prison after the session. However, that night he suffered greatly from side effects, and vomited so much blood that his daughter described as “filled a small bucket” (7). He was allowed to remain in the hospital.

On 15 February 2014, the government issued an order for a 12-month suspension of his prison sentence. From then on, they removed the Public Security guards and the monitoring camera from his room.

On 17 February, they moved him from the palliative care section to Section 4, making him share a bed with three other patients, under terrible conditions. Physicians said that the remaining part of his stomach was like “a jungle and could no longer function”. He could no longer eat because the food could no longer be absorbed, resulting in his vomiting. His kidneys failed more and more.

After a period of intravenous feeding, Mr. Dinh decided to try traditional (oriental) medicine instead of Western medicine. After a few days of using traditional medicine, he got no better.

In mid-March 2014, Mr. Dình’s family took him to Columbia Asia, a private, foreign-owned hospital in Saigon, to seek help for him. Hospital staff put him in intensive care and gave him a comprehensive examination. An endoscopy showed that tumors had re-formed in the remaining part of his stomach (8).

Figure 1. 13 March 2014 endoscopy photo by Columbia Asia Hospital showing newly formed tumors in the remainder of Mr. Dinh’s stomach.

Hospital staff advised the family that there was no more hope to cure him. As Mr. Dinh wished, his family brought him home toDak Nong where he passed away 18 days later on 3 April 2014.

A retrospective look at the patient’s disease progression and his diagnosis and treatment: regrettable failures and unanswered questions

As an impartial observer who is not close to Mr. Dinh, a recap of his disease progression raises a number of obvious questions.

1. Why did it take so long to start examining him and diagnose his illness?

In early November 2011, Mr. Dinh started vomiting and passing blood in his stool. Mrs. Dinh, his wife, recounted: “On 8 of November, I visited my husband in prison. He was bleeding from his stomach. I returned home to write a request to have my husband to be examined and treated at a hospital. I sent the request to prison authorities. However, they only let him be examined and treated at the prison’s medical station. Ms. Thao, Mr. Dinh’s daughter, said that the medical station was merely an isolation cell with a stone platform used as a bed. The only medical equipments consisted of a stethoscope and a blood pressure monitor. The only treatment was an injection to relieve pain in case a patient felt pain, but there was no diagnosis of the root cause. Nothing else was offered in terms of treatment or diagnosis.

Any physician would have felt that a bleeding stomach called for emergency treatment because the symptom indicates an ulcer or even a case of stomach cancer. In serious cases, bleeding from the stomach could lead to fatal hemorrhage if not properly treated on time. Endoscopy would have been the simplest, yet most effective approach to diagnosing the patient. An endoscopy administered in November 2011 would have diagnosed his cancer nearly 2 years earlier, when it was still Stage I or II and not Stage III or IV cancer. Timely treatment would have given him 43,7% to 82% chance for surviving five or more years, depending on whether his cancer was Stage II or I, as the previously mentioned table shows. The most egregious misfortune for him and his family was perhaps the authorities’ complete disregard for the health and life of a prisoner, a disregard that made them blind to Mr. Dinh’s life-threatening symptoms. Prison authorities were wrong as they sent him to the mental hospital in Bien Hoa for two weeks of treatment, believing that his symptoms were more mental than physical.

Colonel Hoan, the warden of An Phuoc Prison, informed the patient’s family: “….based on summary reports No. 78 of 21 October 2013, and No. 96 of 26 November 2013 of the April 30 Hospital…Convict Dinh has stomach cancer that has spread to his lymph nodes (but it is at Stage 3, not yet the final stage)(5)”.Stage III implies that cancer has not spread to nearby organs and only a few lymph nodes are affected, without distant metastasis. A postoperative examination of the stomach section that had been removed and an examination of neighboring lymph nodes in the patient’s body could have shown whether cancer had spread to nearby organs (e.g. the pancreas), and the number of affected lymph nodes. If one wanted to determine the existence of distant metastasis, one should use CT or MRI to examine the lungs and abdomen, and examine the bones by taking scintigrams.

When April 30 Hospital classified Mr. Dinh’s cancer as Stage III, it indirectly pushed him back to the prison in spite of the severity of his disease. The hospital staff did not conduct the examinations cited above (according to Mr. Dinh’s relatives) and therefore could not have determined that Mr. Dinh’s cancer was at Stage III (7). The family’s efforts to obtain his medical records in order to learn more about his diagnosis and treatment were not successful.

The only proper examination he received was at the Cancer Hospital of Saigon. The decision to suspend his prison sentence was probably based on the Cancer Hospital’s diagnosis showing the severity of his disease.

3. Why hadn’t they administered chemotherapy before his operation?

4. Was the removal of ¾ of Mr. Dinh’s stomach a success?

The hospital considered the operation in which ¾ of his stomach had been removed a success once he regained consciousness after the operation. Yet, what did this achieve? Shortly after the operation, his condition got worse and worse. From November 2013, two months after the operation, he again vomited blood. His physician thought that the sutures got infected. However, vomiting blood could be the symptom of something else, namely the operation failed to remove all the cancer cells and cancer continued to spread, causing the remainder of his stomach to bleed. The endoscopy at Columbia Asia Hospital on 13 March 2014 showed a tumor in the remaining portion of the stomach, confirming this hypothesis. This raises the third question: If chemotherapy had been used before the operation to shrink the tumor, perhaps the operation would have removed all the cancer and Mr. Dinh would have been spared the terrible bleeding episodes following the operation that traumatized him and his loved ones. Only the complete removal of all cancerous tissue could have qualified the operation a total success.

5. Why did Mr. Dinh’s kidneys fail?

After the operation, he had been in pain during the last few months of his life, pain caused by terminal stage cancer, compounded by the side effects of chemotherapy. Moreover, shortly after the second chemotherapy session, his failing kidneys caused him considerable difficulty when urinating. Was his kidney condition unrelated to his treatment or a side effect of chemotherapy? The chemicals that destroyed cancer cells could very well have attacked his kidney cells, hampering their function (12).

Whatever the cause of the kidney failure, the problem was like the last link of a chain, with the chain being the progression of symptoms and the patient’s cancer.

6. Why did Mr. Dinh and his relatives have no access to his medical records?

Treatment can be more effective when a patient has sufficient information about his disease. An example is diabetes. Medical personnel not only encourage diabetic patients to learn about their disease, they also coach the patients on learning more and more. Patients with severe cases of cancer have a great desire to learn about their disease. A patient who is knowledgeable about his disease benefits psychologically and his treatment may have a higher chance of success. International research confirmed this fact (4). Mr. Dinh and his family are no exception. When hospital staff withheld medical records and the names of the medicines provided to the patient, without stating the reason for such secrecy, they diminished the patient’s faith in his physicians and medicines. Mr. Dinh refused the third chemotherapy session proposed by April 30 Hospital. Subsequently, after he entered the Cancer Hospital, he left that hospital some time later.Mr. Dinh tried traditional medicine for a period, and later entered a private hospital, Columbia Asia, after he was released from prison. His actions and his relatives’ suspicion of poisoning by prison staff (10) pointed to a profound distrust of the medical care provided by the government and of the government’s respect for the law.

Why does the government withhold a detainee’s medical records? There has been no answer to this question, and the same is true for many other questions related to Vietnam’s important national issues.

The government’s handling of the temporary suspension of the sentence for a very sick prisoner

Colonel Phan Dinh Hoan, the warden of An Phuoc Prison, in a document dated 16 December 2013, cited a document with an unusually long number, Circular 03/2013/TTLT-BCA-TANDTC-VKSNDTC-BQP-BYT issued on 15 May 2013. The circular provided guidance on the procedure for suspending a prisoner’s sentence as follows (5):

Conditions under which a suspension may be considered: “Prisoner’s illness is so severe that he cannot serve his sentence, and if he served it, his life would be in danger. Consequently, a suspension of his sentence should be granted to allow him to receive medical care…This provision applies to severe illnesses such as last stage of cancer, paralysis, tuberculosis that resists antibiotics….cannot independently perform bodily functions, andwhose prognosis is poor, and probability of dying is high, or has been diagnosed with one of the diseases that the medical commission, a provincial hospital or military district hospital (or higher level hospitals) has determined in writing that the patient is in grave danger to his life.”

The circular might have been intended to show mercy in allowing severely sick prisoners to return home for medical care. Until shortly before the document was issued, i.e. before 15 May 2013, did sick prisoners have to serve their sentences until death? However, a close examination of the language of the document reveals that government officials still have much leeway in keeping sick prisoners or releasing them for medical treatment. First, the guidance has no mandatory character: a suspension may be considered(not guaranteed). Second, the government has latitude in defining the severity of sickness. The document cited the last stage of cancer as an example of being gravely ill although many who suffer from breast cancer did survive for several years after being diagnosed with last stage cancer. Prison authorities deemed Stage III cancer with poor prognosis to be not severe enough. The decision showed that prison authorities neglected to consider the varying malignancy and prognosis among different types of cancer. In December 2013 Colonel Hoan relied on the circular to refuse to release Mr. Dinh on the ground that his condition was not yet life threatening. In fact, Mr. Dinh died less than 4 months later, proving that the government’s decision was wrong.

Analyzing past events to avoid future mistakes

Mr. Dinh Dang Dinh has passed away. There are enough facts supporting the belief that he would have lived longer had he been in a prison where authorities were more humane, showed more concern, and allowed timely medical examination and appropriate treatment. There are many gravely ill prisoners of conscience and “regular” prisoners in Vietnam’s prisons. We must not let future tragedies happen like the one that took Mr. Dinh’s life.

The government must show appropriate concern to detainees’ medical symptoms and ensure prompt and sufficient medical examination. Prisons must stop the current practice of cursory examination and prescribing pain-relief medicine without digging into the root cause of such symptoms.

The government must ensure that detainees receive the same level of medical care as other citizens. The government must treat gravely ill prisoners more humanely and enable conditions under which their relatives can care for them and get them proper medical treatment.

The government must give the patients and their loved ones complete information about the disease and the course of treatment, including medicines. It is each patient’s basic right and the right of his/her family to have complete information about his or her disease. The more information a patient has about his/her disease, the higher the probability of cure. Withholding medical information can be construed as a subtle form of mental torture.

Concluding remarks

The author is grateful to Mr. Dinh Dang Dinh’s family and Mr. Vu Quoc Dung

(VETO! Human Rights Defenders’ Network) for their assistance and provision of documents, photos, and other information. While we have tried to use all the resources at our disposal and maintain the highest level of objectivity, there can be omissions and even inaccuracies. A complete and error-free report is possible only after the Vietnamese government releases all of Mr. Dinh’s medical records, at least to his family.

Until then, the government’s lack of humanity in its treatment of prisoners will continue to be an issue in the eyes of many.

This report was prepared in Vietnamese and in German, and will be released in Germany and several other countries. TKT(MRVN).

(*) Remark: the Vietnamese version of this study was posted on http://boxitvn.blogspot.de/2014/05/khi-mot-benh-uoc-dau-kin-nhu-la-bi-mat.html, on May 4, 2014

References

(1)http://www.amnesty.org/en/news/death-activist-dinh-dang-dinh-should-be-wake-call-viet-nam-2014-04-04

(2) An Phuoc Prison’s document No 926-CV/AP, December 24, 2012

(3) http://www.rfa.org/english/news/vietnam/dinh-dang-dinh-12202013161509.html

(4) http://www.krebsgesellschaft.de/download/s3_magenkarzinom_2011_langversion.pdf

(5) An Phuoc Prison’s document No. 907/CV-AP of December 12, 2013

(6) http://www.rfa.org/vietnamese/in_depth/teacher-conscience-in-critical-condition-tt-10082013171218.html

(7) Information from a private source.

(8) Results of endoscopy performed on March 13, 2013, Klinik ColumbiaAsia, Saigon

(9) http://www.rfa.org/vietnamese/in_depth/teacher-conscience-in-critical-condition-tt-10082013171218.

(10) htmlp://www.bbc.co.uk/vietnamese/vietnam/2014/04/140405_dinhdangdinh_funeral.shml

(11)http://www.pathologie-guetersloh.de/informationen/leitlinien-empfehlungen-und/magen-git-leitlinien-empfeh/s3-leitlinie-magenkarzinom.pdf (66. Empfehlung)

(12)http://http://www.krebsinformationsdienst.de/behandlung/chemotherapie-nebenwirkungen.php

(13)www.krebsinformationsdienst.de/tumorarten/magenkrebs/behandlungsverfahren.php#inhalt17