Foreign Policy, December 01, 2016

Corruption, graft, and palm-greasing are a real and growing drag on the global economy — and they open the door to a host of evils like drug smuggling and human trafficking. Bribes to the tune of about $1.5 trillion change hands every year, according to the International Monetary Fund, or about 5 percent of global GDP.

And the true cost of corruption doesn’t just boil down to money, either. “You can’t have narco-trafficking without bribery, human trafficking without bribery, or even terrorism without bribery,” said Alexandra Wrage, president and founder of the anti-bribery organization TRACE International.

TRACE says that bribery is getting worse, with global graft on the rise, according to a new study. Some 60 percent of countries have an increased bribery risk compared with the 2014 study, while only 32 percent have a decreased bribery risk, the group says. While anti-bribery laws and enforcement are on the upswing in many countries, government transparency and capacity for civil society oversight of anti-bribery are not.

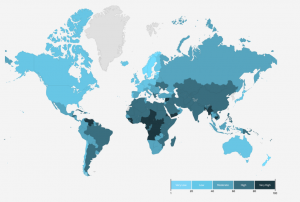

The study shows the cleanest — and most graft-prone — countries around the world, ranking countries on a scale of 1 to 100, with higher numbers indicating higher bribery risks.

See how each country stacks up here:

Sweden comes out on top with a score of 10, followed by New Zealand at 15 and Estonia at 17. The most bribery-prone country in the world is Nigeria, with a score of 99. Russia is actually getting cleaner, TRACE says, improving from a score of 65 two years ago to 58 today. China, despite a huge anti-corruption drive in Beijing, sits immobile with a score of 66.

Even the United States even saw a slight increase in bribery risk, going from a score of 27 in 2014 to a score of 34 in 2016, though it’s still a lot closer to Sweden than Swaziland. The United States improved anti-bribery laws, according to the study, but saw its score rise because of increased business-to-government interactions and a slight backslide in civil society oversight of bribery.

“Generally, more places have gotten worse than have gotten better,” Virna Di Palma, senior director of global strategy with TRACE, told Foreign Policy. In particular, the Americas, Africa, and East Asia are backsliding on fighting corruption, Di Palma said.

Corruption hemorrhages public trust in governments. A Transparency International study released in November found, after surveying 60,000 Europeans and Central Asians, 53 percent thought their governments handled corruption poorly, while only 23 percent thought they were doing well. One in three surveyed thought their government’s officials and lawmakers were mostly corrupt. Even in the supposedly cleaner and more advanced West, public ire at corruption — whether real or perceived — helps fuel populist political movements.

All is not necessarily lost, though, says Wrage. Corporate behavior is getting more legal scrutiny around the world. And if bribery scores are high now, it may be because bribery was simply more difficult to track in the past. “It’s not that there’s more bribery, it’s that it’s more visible,” Wrage said.

Companies are also learning that dirty business can be bad business, says Di Palma. Additionally, small and medium-sized companies — not just multinationals — are beginning to take anti-graft measures more seriously.

“We see the world trending in the right direction,” Di Palma said. “Initially companies were only interested because of increased anti-bribery enforcement, but in the last few years we’ve seen a change,” she said, adding that “companies are recognizing that bribery is a bad business strategy.”

Height Insoles: Hi, I do believe this is an excellent site. I stumbledupon …

http://fishinglovers.net: Appreciate you sharing, great post.Thanks Again. Keep writi…

Achilles Pain causes: Every weekend i used to pay a quick visit this site, as i w…

December 4, 2016

Bribery Is on the Rise Worldwide, and It Costs A Lot More Than Just Money

by Nhan Quyen • [Human Rights]

Foreign Policy, December 01, 2016

Corruption, graft, and palm-greasing are a real and growing drag on the global economy — and they open the door to a host of evils like drug smuggling and human trafficking. Bribes to the tune of about $1.5 trillion change hands every year, according to the International Monetary Fund, or about 5 percent of global GDP.

And the true cost of corruption doesn’t just boil down to money, either. “You can’t have narco-trafficking without bribery, human trafficking without bribery, or even terrorism without bribery,” said Alexandra Wrage, president and founder of the anti-bribery organization TRACE International.

TRACE says that bribery is getting worse, with global graft on the rise, according to a new study. Some 60 percent of countries have an increased bribery risk compared with the 2014 study, while only 32 percent have a decreased bribery risk, the group says. While anti-bribery laws and enforcement are on the upswing in many countries, government transparency and capacity for civil society oversight of anti-bribery are not.

The study shows the cleanest — and most graft-prone — countries around the world, ranking countries on a scale of 1 to 100, with higher numbers indicating higher bribery risks.

See how each country stacks up here:

Sweden comes out on top with a score of 10, followed by New Zealand at 15 and Estonia at 17. The most bribery-prone country in the world is Nigeria, with a score of 99. Russia is actually getting cleaner, TRACE says, improving from a score of 65 two years ago to 58 today. China, despite a huge anti-corruption drive in Beijing, sits immobile with a score of 66.

Even the United States even saw a slight increase in bribery risk, going from a score of 27 in 2014 to a score of 34 in 2016, though it’s still a lot closer to Sweden than Swaziland. The United States improved anti-bribery laws, according to the study, but saw its score rise because of increased business-to-government interactions and a slight backslide in civil society oversight of bribery.

“Generally, more places have gotten worse than have gotten better,” Virna Di Palma, senior director of global strategy with TRACE, told Foreign Policy. In particular, the Americas, Africa, and East Asia are backsliding on fighting corruption, Di Palma said.

Corruption hemorrhages public trust in governments. A Transparency International study released in November found, after surveying 60,000 Europeans and Central Asians, 53 percent thought their governments handled corruption poorly, while only 23 percent thought they were doing well. One in three surveyed thought their government’s officials and lawmakers were mostly corrupt. Even in the supposedly cleaner and more advanced West, public ire at corruption — whether real or perceived — helps fuel populist political movements.

All is not necessarily lost, though, says Wrage. Corporate behavior is getting more legal scrutiny around the world. And if bribery scores are high now, it may be because bribery was simply more difficult to track in the past. “It’s not that there’s more bribery, it’s that it’s more visible,” Wrage said.

Companies are also learning that dirty business can be bad business, says Di Palma. Additionally, small and medium-sized companies — not just multinationals — are beginning to take anti-graft measures more seriously.

“We see the world trending in the right direction,” Di Palma said. “Initially companies were only interested because of increased anti-bribery enforcement, but in the last few years we’ve seen a change,” she said, adding that “companies are recognizing that bribery is a bad business strategy.”