The analysis found that less than 14 percent of the world’s inhabitants lived in countries with a Free press, while 43 percent had a Partly Free press and 43 percent lived in Not Free environments. The population figures are significantly affected by two countries—China, with a Not Free status, and India, with a Partly Free status—that together account for over a third of the world’s nearly seven billion people.

Freedome House | May 1, 2014

Middle East Volatility amid Global Decline

Ongoing political turmoil produced uneven conditions for press freedom in the Middle East in 2012, with Tunisia and Libya largely retaining their gains from 2011 even as Egypt slid backward into the Not Free category. The region as a whole experienced a net decline for the year, in keeping with a broader global pattern in which the percentage of people worldwide who enjoy a free media environment fell to its lowest point in more than a decade. Among the more disturbing developments in 2012 were dramatic declines for Mali, significant deterioration in Greece, and a further tightening of controls on press freedom in Latin America, punctuated by the decline of two countries, Ecuador and Paraguay, from Partly Free to Not Free status.

These were the most significant findings of Freedom of the Press 2013: A Global Survey of Media Independence, the latest edition of an annual index published by Freedom House since 1980. While there were positive developments in Burma, the Caucasus, parts of West Africa, and elsewhere, the dominant trends were reflected in setbacks in a range of political settings. Reasons for decline included the continued, increasingly sophisticated repression of independent journalism and new media by authoritarian regimes; the ripple effects of the European economic crisis and longer-term challenges to the financial sustainability of print media; and ongoing threats from nonstate actors such as radical Islamists and organized crime groups.

The trend of overall decline occurred, paradoxically, in a context of increasingly diverse news sources and ever-expanding means of political communication. The growth of these new media has triggered a repressive backlash by authoritarian regimes that have carefully controlled television and other mass media and are now alert to the dangers of unfettered political commentary online. Influential powers—such as China, Russia, Iran, and Venezuela—have long resorted to a variety of techniques to maintain a tight grip on the media, detaining some press critics, closing down or otherwise censoring media outlets and blogs, and bringing libel or defamation suits against journalists. Russia, which adopted additional restrictions on internet content in 2012, set a negative tone for the rest of Eurasia, where conditions remained largely grim. In China, the installation of a new Communist Party leadership did not produce any immediate relaxation of constraints on either traditional media or the internet. In fact, the Chinese regime, which boasts the world’s most intricate and elaborate system of media repression, stepped up its drive to limit both old and new sources of information through arrests and censorship.

This infographic highlights countries with notable developments for press freedom during the past year.

To see a full-screen version of the infographic, click here.

As a result of declines in both authoritarian and democratic settings over the past several years, the proportion of the global population that enjoys a Free press has fallen to its lowest level in over a decade. The report found that less than 14 percent of the world’s people—or roughly one in six—live in countries where coverage of political news is robust, the safety of journalists is guaranteed, state intrusion in media affairs is minimal, and the press is not subject to onerous legal or economic pressures. Moreover, in the most recent five-year period, significant country declines have far outnumbered gains, suggesting that attempts to restrict press freedom are widespread and challenges to expanding media diversity and access to information remain considerable.

There were some promising developments during the year to partially offset these worrisome trends. Positive movement occurred in a number of key countries in Asia (Afghanistan and Burma), Eurasia (Armenia and Georgia), and sub-Saharan Africa (Côte d’Ivoire, Liberia, Malawi, Mauritania, Senegal, and Zimbabwe), as well as in Yemen. Many advances occurred in the context of new governments that either rolled back restrictive legal and regulatory provisions or allowed greater space for vibrant and critical media to operate. Particularly noteworthy was the continued dramatic opening in Burma, which registered the survey’s largest numerical improvement of the year due to people’s increased ability to access information and the release of imprisoned bloggers and video journalists, among other factors.

Of the 197 countries and territories assessed during 2012, a total of 63 (32 percent) were rated Free, 70 (36 percent) were rated Partly Free, and 64 (32 percent) were rated Not Free. This balance marks a shift toward the Not Free category compared with the edition covering 2011, which featured 66 Free, 72 Partly Free, and 59 Not Free countries and territories.

The analysis found that less than 14 percent of the world’s inhabitants lived in countries with a Free press, while 43 percent had a Partly Free press and 43 percent lived in Not Free environments. The population figures are significantly affected by two countries—China, with a Not Free status, and India, with a Partly Free status—that together account for over a third of the world’s nearly seven billion people. The percentage of those enjoying Free media in 2012 declined by another half point to the lowest level since 1996, when Freedom House began incorporating population data into the findings of the survey. Meanwhile, the share living in Not Free countries jumped by 2.5 percentage points, reflecting the move by populous states such as Egypt and Thailand back into that category.

Continue reading essay

Freedom of the Press 2013 Release Materials:

Full 2013 Report

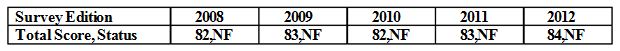

Vietnam

- Status: Not Free

- Legal Environment: 29

- Political Environment: 33

- Economic Environment: 22

- Total Score: 84

Vietnam remained one of Asia’s harshest environments for the press in 2012. Authorities continued to employ both legal attacks and physical harassment to punish and intimidate journalists critical of the government, led by the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV). The internet remains one of the few spaces for dissent, though crackdowns on both high-profile and more obscure outlets have sent a chill through the blogosphere. However, the presence of some public discussion in state-owned media and online blogs on constitutional and land reform is promising.

Although the 1992 constitution recognizes freedom of expression, the criminal code prohibits speech that is critical of the government. The definition of such speech is vaguely worded and broadly interpreted. The propaganda and training departments of the CPV control all media and set press guidelines. The government frequently levies charges under Article 88 of the criminal code, which prohibits the dissemination of “antigovernment propaganda,” as well as Article 79, a broad ban on activities aimed at “overthrowing the state.” Reacting to increasingly vibrant reporting by both the traditional and internet-based news media, the government issued a decree in 2006 that defined over 2,000 additional violations of the law in the areas of culture and information, with a particular focus on protecting “national security.” In January 2011, Prime Minister Nguyễn Tấn Dũng signed Decree No. 2, Sanctions for Administrative Violations in Journalism and Publishing, restricting the use of pseudonyms and anonymous sources and excluding bloggers from press freedom protections. During 2012, the government was reportedly drafting a Decree on the Management, Provision, Use of Internet Services and Internet Content Online. Designed to prohibit anonymity and “abuse” of the internet, it prompted concerns over increased legal mechanisms to criminalize dissent.

The judiciary is not independent. Individuals are held for months or longer in pretrial detention and are sometimes not released after completing their sentences. Many trials related to free expression last only a few hours. In August 2012, a Đăk Nông provincial court sentenced netizen Đinh Đăng Định to six years in prison for articles critical of corruption and bauxite mining. Also that month, Lê Thanh Tùng of the activist group Bloc 8406 was sentenced in a one-hour trial in Hanoi to five years imprisonment for articles calling fo rmultiparty democracy. In September, a Ho Chi Minh City court convicted popular bloggers and founders of the Free Journalists Club Nguyễn Văn Hải, Tạ Phong Tần, and Phan Thanh Hải of antigovernment propaganda. Nguyễn Văn Hải, who writes under the name “Điếu Cày,” was sentenced to 12 years in prison for reporting on anti-Chinese protests. He has remained in prison, held largely incommunicado, since completing a previous sentence in October 2010 for trumped-up charges of tax evasion. Tạ Phong Tần was sentenced to 10 years and Phan Thanh Hải to 4. With 14 netizens imprisoned at year’s end, Vietnam has one of the largest numbers of bloggers behind bars worldwide.

The CPV generally views the media as a tool for the dissemination of party and state policy. Calls for democratic reform and religious freedom, land rights, and criticism of relations with China are the issues most commonly targeted for official censorship or retribution. Provincial-level media enjoy slightly more room to report on local issues and have recently provided increased coverage of land laws and constitutional reforms. In the past, journalists have occasionally been permitted to report on corruption at the local level, as it serves the interests of the party’s national anticorruption platform. However, in September a Ho Chi Minh City court sentenced well-known Tuổi Trẻ corruption reporter Nguyễn Văn Khương to four years in prison for bribing a police officer as part of an undercover investigation.

Censorship of online content is increasingly common. Internet service providers (ISPs) are legally required to block access to websites that are considered politically unacceptable, and in 2008, the Ministry of Information and Communications (MIC) formed an agency to monitor the internet and blogosphere. In September 2012, Prime Minister Dũng issued an executive order to investigate antigovernment blog Dân Làm Báo and two other online outlets. Though the government has denied using cyberattacks to monitor and prevent dissident activity, malicious programs attached to downloadable Vietnamese-language software and distributed denial-of- service (DDoS) attacks, which overwhelm servers and websites with traffic, frequently target politically sensitive websites.

Police often use violence, intimidation, and raids of homes and offices to silence journalists who report on sensitive topics. Police severely beat state-run Voice of Vietnam

(VOV) journalists Nguyễn Ngọc Năm and Hán Phi Long in April 2012 while the two were covering protests of mass evictions in Hưng Yên province. Numerous reports of plainclothes police harassing the families of imprisoned journalists and preventing bloggers’ family members from attending trials surfaced throughout the year. Several bloggers were detained at, or prevented from accessing, anti-China protests in July and December. Foreign reporters have been denied entry into the country after reporting on politically sensitive topics. The government did pass a promising decree on October 23, however, which expands visa permissions for foreign journalists and allows for the first time foreign press agencies to establish a presence outside Hanoi, the capital.

Almost all print media outlets are owned or controlled by the CPV, government institutions, or the army. Several of these newspapers—including Thanh Niên, Người Lao Động, and Tuổi Trẻ (owned by the CPV Youth Union)—have attempted to become financially self sustaining. Along with the popular online news site VietnamNet, they have a fair degree of editorial independence, though ultimately they are subject to the CPV’s supervision. Several underground publications have been launched in recent years, including Tổ Quốc, which continues to circulate despite harassment of staff members, and Tự Do Ngôn Luận, whose editor, Father Nguyễn Văn Lý, is currently serving an eight-year prison sentence. Radio is controlled by the VOV or other state entities. State-owned Vietnam Television (VTV) is the only national television provider, although cable services do carry some foreign channels. Many homes and local businesses in urban areas have satellite dishes, allowing them to access foreign programming. In 2011, Decision 20/2011 came into effect, requiring all foreign news, education, and information television content to be translated into Vietnamese and censored by the MIC before airing. International periodicals, though widely available, are sometimes censored. The Vietnamese-language services of the British Broadcasting Corporation, Voice of America, and Radio Free Asia are also blocked intermittently.

Approximately 40 percent of the population accessed the internet in 2012, with the vast majority utilizing internet cafés and other public providers. Website operators continue to use ISPs that are either wholly or partly state-owned. The largest is Vietnam Data Communications, which is controlled by the state-owned Vietnam Posts and Telecommunications Group and serves nearly a third of all internet users. Rising internet penetration has created opportunities for discussion and debate about salient public issues, including land rights and environmental concerns. This has posed problems for the CPV, which seeks to promote new technology while restricting online criticism.

See full report here: FOTP 2013 Full Report

Height Insoles: Hi, I do believe this is an excellent site. I stumbledupon …

http://fishinglovers.net: Appreciate you sharing, great post.Thanks Again. Keep writi…

Achilles Pain causes: Every weekend i used to pay a quick visit this site, as i w…

May 3, 2014

Freedom of the Press 2013

by HR Defender • [Human Rights]

Freedome House | May 1, 2014

Middle East Volatility amid Global Decline

Ongoing political turmoil produced uneven conditions for press freedom in the Middle East in 2012, with Tunisia and Libya largely retaining their gains from 2011 even as Egypt slid backward into the Not Free category. The region as a whole experienced a net decline for the year, in keeping with a broader global pattern in which the percentage of people worldwide who enjoy a free media environment fell to its lowest point in more than a decade. Among the more disturbing developments in 2012 were dramatic declines for Mali, significant deterioration in Greece, and a further tightening of controls on press freedom in Latin America, punctuated by the decline of two countries, Ecuador and Paraguay, from Partly Free to Not Free status.

These were the most significant findings of Freedom of the Press 2013: A Global Survey of Media Independence, the latest edition of an annual index published by Freedom House since 1980. While there were positive developments in Burma, the Caucasus, parts of West Africa, and elsewhere, the dominant trends were reflected in setbacks in a range of political settings. Reasons for decline included the continued, increasingly sophisticated repression of independent journalism and new media by authoritarian regimes; the ripple effects of the European economic crisis and longer-term challenges to the financial sustainability of print media; and ongoing threats from nonstate actors such as radical Islamists and organized crime groups.

The trend of overall decline occurred, paradoxically, in a context of increasingly diverse news sources and ever-expanding means of political communication. The growth of these new media has triggered a repressive backlash by authoritarian regimes that have carefully controlled television and other mass media and are now alert to the dangers of unfettered political commentary online. Influential powers—such as China, Russia, Iran, and Venezuela—have long resorted to a variety of techniques to maintain a tight grip on the media, detaining some press critics, closing down or otherwise censoring media outlets and blogs, and bringing libel or defamation suits against journalists. Russia, which adopted additional restrictions on internet content in 2012, set a negative tone for the rest of Eurasia, where conditions remained largely grim. In China, the installation of a new Communist Party leadership did not produce any immediate relaxation of constraints on either traditional media or the internet. In fact, the Chinese regime, which boasts the world’s most intricate and elaborate system of media repression, stepped up its drive to limit both old and new sources of information through arrests and censorship.

This infographic highlights countries with notable developments for press freedom during the past year.

To see a full-screen version of the infographic, click here.

As a result of declines in both authoritarian and democratic settings over the past several years, the proportion of the global population that enjoys a Free press has fallen to its lowest level in over a decade. The report found that less than 14 percent of the world’s people—or roughly one in six—live in countries where coverage of political news is robust, the safety of journalists is guaranteed, state intrusion in media affairs is minimal, and the press is not subject to onerous legal or economic pressures. Moreover, in the most recent five-year period, significant country declines have far outnumbered gains, suggesting that attempts to restrict press freedom are widespread and challenges to expanding media diversity and access to information remain considerable.

There were some promising developments during the year to partially offset these worrisome trends. Positive movement occurred in a number of key countries in Asia (Afghanistan and Burma), Eurasia (Armenia and Georgia), and sub-Saharan Africa (Côte d’Ivoire, Liberia, Malawi, Mauritania, Senegal, and Zimbabwe), as well as in Yemen. Many advances occurred in the context of new governments that either rolled back restrictive legal and regulatory provisions or allowed greater space for vibrant and critical media to operate. Particularly noteworthy was the continued dramatic opening in Burma, which registered the survey’s largest numerical improvement of the year due to people’s increased ability to access information and the release of imprisoned bloggers and video journalists, among other factors.

Of the 197 countries and territories assessed during 2012, a total of 63 (32 percent) were rated Free, 70 (36 percent) were rated Partly Free, and 64 (32 percent) were rated Not Free. This balance marks a shift toward the Not Free category compared with the edition covering 2011, which featured 66 Free, 72 Partly Free, and 59 Not Free countries and territories.

The analysis found that less than 14 percent of the world’s inhabitants lived in countries with a Free press, while 43 percent had a Partly Free press and 43 percent lived in Not Free environments. The population figures are significantly affected by two countries—China, with a Not Free status, and India, with a Partly Free status—that together account for over a third of the world’s nearly seven billion people. The percentage of those enjoying Free media in 2012 declined by another half point to the lowest level since 1996, when Freedom House began incorporating population data into the findings of the survey. Meanwhile, the share living in Not Free countries jumped by 2.5 percentage points, reflecting the move by populous states such as Egypt and Thailand back into that category.

Continue reading essay

Freedom of the Press 2013 Release Materials:

Full 2013 Report

Vietnam

Vietnam remained one of Asia’s harshest environments for the press in 2012. Authorities continued to employ both legal attacks and physical harassment to punish and intimidate journalists critical of the government, led by the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV). The internet remains one of the few spaces for dissent, though crackdowns on both high-profile and more obscure outlets have sent a chill through the blogosphere. However, the presence of some public discussion in state-owned media and online blogs on constitutional and land reform is promising.

Although the 1992 constitution recognizes freedom of expression, the criminal code prohibits speech that is critical of the government. The definition of such speech is vaguely worded and broadly interpreted. The propaganda and training departments of the CPV control all media and set press guidelines. The government frequently levies charges under Article 88 of the criminal code, which prohibits the dissemination of “antigovernment propaganda,” as well as Article 79, a broad ban on activities aimed at “overthrowing the state.” Reacting to increasingly vibrant reporting by both the traditional and internet-based news media, the government issued a decree in 2006 that defined over 2,000 additional violations of the law in the areas of culture and information, with a particular focus on protecting “national security.” In January 2011, Prime Minister Nguyễn Tấn Dũng signed Decree No. 2, Sanctions for Administrative Violations in Journalism and Publishing, restricting the use of pseudonyms and anonymous sources and excluding bloggers from press freedom protections. During 2012, the government was reportedly drafting a Decree on the Management, Provision, Use of Internet Services and Internet Content Online. Designed to prohibit anonymity and “abuse” of the internet, it prompted concerns over increased legal mechanisms to criminalize dissent.

The judiciary is not independent. Individuals are held for months or longer in pretrial detention and are sometimes not released after completing their sentences. Many trials related to free expression last only a few hours. In August 2012, a Đăk Nông provincial court sentenced netizen Đinh Đăng Định to six years in prison for articles critical of corruption and bauxite mining. Also that month, Lê Thanh Tùng of the activist group Bloc 8406 was sentenced in a one-hour trial in Hanoi to five years imprisonment for articles calling fo rmultiparty democracy. In September, a Ho Chi Minh City court convicted popular bloggers and founders of the Free Journalists Club Nguyễn Văn Hải, Tạ Phong Tần, and Phan Thanh Hải of antigovernment propaganda. Nguyễn Văn Hải, who writes under the name “Điếu Cày,” was sentenced to 12 years in prison for reporting on anti-Chinese protests. He has remained in prison, held largely incommunicado, since completing a previous sentence in October 2010 for trumped-up charges of tax evasion. Tạ Phong Tần was sentenced to 10 years and Phan Thanh Hải to 4. With 14 netizens imprisoned at year’s end, Vietnam has one of the largest numbers of bloggers behind bars worldwide.

The CPV generally views the media as a tool for the dissemination of party and state policy. Calls for democratic reform and religious freedom, land rights, and criticism of relations with China are the issues most commonly targeted for official censorship or retribution. Provincial-level media enjoy slightly more room to report on local issues and have recently provided increased coverage of land laws and constitutional reforms. In the past, journalists have occasionally been permitted to report on corruption at the local level, as it serves the interests of the party’s national anticorruption platform. However, in September a Ho Chi Minh City court sentenced well-known Tuổi Trẻ corruption reporter Nguyễn Văn Khương to four years in prison for bribing a police officer as part of an undercover investigation.

Censorship of online content is increasingly common. Internet service providers (ISPs) are legally required to block access to websites that are considered politically unacceptable, and in 2008, the Ministry of Information and Communications (MIC) formed an agency to monitor the internet and blogosphere. In September 2012, Prime Minister Dũng issued an executive order to investigate antigovernment blog Dân Làm Báo and two other online outlets. Though the government has denied using cyberattacks to monitor and prevent dissident activity, malicious programs attached to downloadable Vietnamese-language software and distributed denial-of- service (DDoS) attacks, which overwhelm servers and websites with traffic, frequently target politically sensitive websites.

Police often use violence, intimidation, and raids of homes and offices to silence journalists who report on sensitive topics. Police severely beat state-run Voice of Vietnam

(VOV) journalists Nguyễn Ngọc Năm and Hán Phi Long in April 2012 while the two were covering protests of mass evictions in Hưng Yên province. Numerous reports of plainclothes police harassing the families of imprisoned journalists and preventing bloggers’ family members from attending trials surfaced throughout the year. Several bloggers were detained at, or prevented from accessing, anti-China protests in July and December. Foreign reporters have been denied entry into the country after reporting on politically sensitive topics. The government did pass a promising decree on October 23, however, which expands visa permissions for foreign journalists and allows for the first time foreign press agencies to establish a presence outside Hanoi, the capital.

Almost all print media outlets are owned or controlled by the CPV, government institutions, or the army. Several of these newspapers—including Thanh Niên, Người Lao Động, and Tuổi Trẻ (owned by the CPV Youth Union)—have attempted to become financially self sustaining. Along with the popular online news site VietnamNet, they have a fair degree of editorial independence, though ultimately they are subject to the CPV’s supervision. Several underground publications have been launched in recent years, including Tổ Quốc, which continues to circulate despite harassment of staff members, and Tự Do Ngôn Luận, whose editor, Father Nguyễn Văn Lý, is currently serving an eight-year prison sentence. Radio is controlled by the VOV or other state entities. State-owned Vietnam Television (VTV) is the only national television provider, although cable services do carry some foreign channels. Many homes and local businesses in urban areas have satellite dishes, allowing them to access foreign programming. In 2011, Decision 20/2011 came into effect, requiring all foreign news, education, and information television content to be translated into Vietnamese and censored by the MIC before airing. International periodicals, though widely available, are sometimes censored. The Vietnamese-language services of the British Broadcasting Corporation, Voice of America, and Radio Free Asia are also blocked intermittently.

Approximately 40 percent of the population accessed the internet in 2012, with the vast majority utilizing internet cafés and other public providers. Website operators continue to use ISPs that are either wholly or partly state-owned. The largest is Vietnam Data Communications, which is controlled by the state-owned Vietnam Posts and Telecommunications Group and serves nearly a third of all internet users. Rising internet penetration has created opportunities for discussion and debate about salient public issues, including land rights and environmental concerns. This has posed problems for the CPV, which seeks to promote new technology while restricting online criticism.

See full report here: FOTP 2013 Full Report